For a number of years now, on Christmas Eve, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporations has rebroadcast a recording of Alan Maitland reading Fredrick Forsyth’s, “The Shepherd”. Maitland was the host of a very popular CBC program called “As it Happens” in the 1980’s and his voice seems perfect for reading Forsyth’s story of a RAF pilot flying from Germany back to England on Christmas Eve, 1957, when his jet suffers a complete electrical failure. Lost in the clouds and fog, and low on fuel, he is met or led or “shepherded” to a disused WW2 era RAF base by a WW2 De Havilland Mosquito which he believes has been sent up to bring him in before he crashes.

As the story unfolds, he learns that the pilot was named Johnny Kavanaugh and he learns that Kavanaugh had a lot of practice shepherding damaged bombers back to the RAF base during the war. We also learn that Kavanaugh’s Mosquito Squadron was a Pathfinder squadron during the war.

As I was listening to the story this year, I was reminded that one of my uncle’s who passed away in the 1980’s had flown in a Pathfinder squadron during the war. The job of the Pathfinders was to lead the bombing raid and mark the targets for the bombers that were following behind. The Pathfinders dropped green and red colored flares to mark the periphery of where they thought the target was. If they did a good job, the results of the bombing mission would be a success. If they did a bad job, the raid might be a complete waste of time as the bombs could fall easily wide of their intended target.

My Uncle, Allan Gonor, received a Distinguished Flying Cross for completing 38 missions as a navigator between September 16, 1944 and March 31, 1945. Unlike the Pathfinder in the Forsyth story, Allan’s squadron did not fly the amazingly fast Mosquito but instead his Pathfinder squadron flew the famous 4 engine Lancaster Bomber.

Lancasters used as pathfinders, flew with a crew of 8 but just one pilot. Below summarizes the crew assignments:

| Position | Location |

| Pilot | Seated on the left hand side of the cockpit. There was no Co-Pilot |

| Flight Engineer | Seated next to the pilot on a folding seat |

| Navigator | Seated at a table facing to the port (left) of the aircraft and directly behind the pilot and flight engineer |

| Navigator/Radar Operator | Seated next to the navigator and also facing to the port (left) of the aircraft the Special Equipment Operator operated the H2S radar set |

| Bomb Aimer | Seated when operating the front gun turret, but positioned in a laying position when directing the pilot on to the aiming point prior to releasing the bomb load |

| Wireless Operator | Seated facing forward and directly beside the navigator |

| Mid-Upper Gunner | Seated in the mid upper turret, which was also in the unheated section of the fuselage |

| Rear Gunner | “Tail End Charlie” seated in the rear turret this to was in the unheated section of the fuselage and was also the most isolated position. Most rear gunner’s once in their turret’s did not see another member of the crew until the aircraft returned to base, sometimes 10 hours after departing |

My cousin Saul had a copy of Allan’s DFC citation which listed all the various raids that comprised his 38 qualifying missions. As I began going through the list, I quickly came to realize that some of the raids in which Allan flew as a Pathfinder were some of the most historically interesting raids of the war.

Allan, arrived in England from Canada in 1943 after graduating from Navigator School at the ripe old age of 18. Although he was Canadian, he never flew in the RCAF but instead spent the war flying in various RAF Squadrons.

Initially he seems to have been involved in some sort of replacement pool of airmen as his first missions seem to indicate that he was moving from one squadron to another.

His first mission is listed as occurring on 16 Sep 44 when he flew with the 101 Squadron to Leeuwarden in Nazi occupied Holland. History records that the British heavily attacked this Dutch airfield on the 16 and 17th of Sep of 1944 as it was being used by the Nazis to house Messerschmidt Bf-109’s. This date is significant as the raid was timed to coincide with the beginning of Operation Market-Garden which began on September 17. Keep in mind that the British typically bombed at night. This meant Allan’s flight began on September 16 after sundown and he returned to base after midnight on September 17. Thus, Allan’s first raid was really timed for the same day as the beginning of Operation Market-Garden.

On September 27 and 28, Allan flew missions in the 158 Squadron to Calais in support of the Canadian Army which was fighting its way northwards from Normandy towards Antwerp.

On 2 Oct 44, he flew with the 12 Squadron to Westkapelle in Holland. Westkapelle is west of Antwerp and history records that on the night of Oct 2/3, the British bombed the dikes south of the town to flood the area so that the Germans could not move around as the Canadian Army began to attack the place from the ground.

In October of 1944, Allan spent most of his time with the 101st Squadron. This squadron of Lancasters was special in that the planes were modified to carry a large radio transmitter and a 2nd radio operator who spoke fluent German. Their mission was to confuse the German fighters by issuing instructions in German trying to vector the attacking German fighters AWAY from the British bombers. They also carried powerful radio jammers to try to jam the German’s radio communications. Since they were broadcasting all the time, their positions could be ascertained by the the Germans using radio direction finding equipment and by triangulating their positions. This made flying in these planes very dangerous and many of them were shot down as they were prime targets for the German night fighters.

It was during this month that Allan participated in his first 1000+ plane raid to Dusiburg on 14 Oct 44. Unbelievably, the RAF attacked Duisburg twice on the same day; during the day and then again that same evening. Allan was on both raids. More than 1/2 the city was destroyed as the RAF tried to take out a synthetic fuel plant, among other targets. The Germans had very few oil resources. Most of the fuel that they burned in their tanks, their trucks and their planes was manufactured by liquifying coal. They built many of these plants and each of them was a prime target for Bomber Command. On each raid that day to Duisburg, the RAF lost more than 100 planes to flak and to enemy fighters.

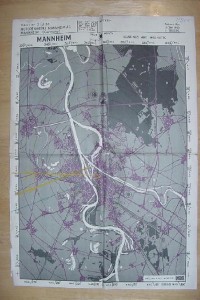

In November, Allan was assigned to the Pathfinder Squadron #156 where he remained for the duration of the war. He flew 24 more raids with the 156 Squadron and had nearly the same crew each time. They seemed to change planes frequently and the flying log notes that they often returned to base with a lot of holes in the plane so its no wonder they had to change aircraft. Allan was part of a permanent team that included another Canadian, who like Allan, was flying in the RAF rather than the RCAF. The pilot of the crew was Arthur Boggiano. Boggiano received his DFC for having the nerve to continue to lead a mission to Mannheim on 1 Mar 45 where they lost an engine before they even arrived at the target. Despite just having 3 functioning engines and instead of turning around and returning to base, Boggiano and his crew continued to Mannheim, marked the target, and dropped their own bomb load from just 6800 ft (while everyone else was bombing from 18000 ft) before beginning the long flight home. This was not a night raid but a day raid. Their log shows that they departed their base at 12:25. They were over the target at 15:14 (3:14 pm) and they arrived back at their base at 18:50, more than 1 hour late due to their reduced speed from the loss of the engine. Interestingly, the log also notes that they were “shepherded” back to base by fighters that found them as they were flying west and flying alone over the North Sea. For his effort that day, Boggiano was awarded the DFC.

One of Allan’s missions in particular jumped right off the page for me. On the nights of 13 and 14 Feb 45, the British and the US bombed Dresden with devastating results. Sure enough, this mission is on Allan’s list. He flew that first night, on 13 Feb 45 as one of the lead Pathfinders. Their log notes that as they approached the target, the fires in Dresden were already visible from 60 miles away.

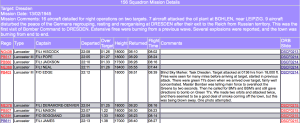

The log bears reading below:  “Extensive fires were burning from a previous wave. Several explosions were reported, and the town was burning from end to end”.

“Extensive fires were burning from a previous wave. Several explosions were reported, and the town was burning from end to end”.

Allan’s final mission occurred on 30 Apr 45 when he participated in something called Operation Manna. During Operation Market-Garden in September of 1944, the Dutch railway workers went on strike in support of the allied effort. To retaliate, the Germans banned all food imports into Holland. With the onset of what was to become the harshest European winter in 30 years, the Dutch began to starve in what became known as the “Hunger Winter”. By the spring, hundreds were dying of starvation each day. Despite significant parts of Holland being liberated by the Canadians, the northern and western parts of Holland remained occupied by the German Army right up until the final surrender in May of 1945. In the final few days of the war, the Germans and the Allies were trying to negotiate an arrangement whereby the Allies could drop food to the starving Dutch. As the negotiations dragged on, the RAF took a chance that the Germans would not shoot down low flying bombers dropping food from 300 ft to the Dutch. On April 30, they sent 300+ planes including Allan’s Pathfinder Squadron to Rotterdam where they opened the bomb bay doors and dropped food instead of the usual bombs.

Cristian de Groot from Holland found this 8 mm footage of what the drop looked like from the ground. http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2011/04/rare_footage_of_rotterdam_food.php/

The planes you see in the footage are Lancaster Bombers. Perhaps one of them is Allan’s?

I also had another uncle who flew in bombers during WW2. My mother’s brother, Dave Elkin, was also a navigator. He flew in the RCAF in a Halifax Bomber. Both the Halifax and the Lancaster were 4 engine bombers but the Lancaster had a slightly larger bomb load and could fly higher and further than the Halifax. Both had a standard crew compliment of 7 men. Dave flew 26 missions in the RCAF 408 Squadron beginning on 04 Oct 44 to Dortmund. His final mission was to Hannover on 05 Jan 45 where his Halifax was shot down. Dave bailed out and spent the last 6 months of the war in a POW camp near Lukenwalde, south and west of Berlin. Dave and Allan never knew each other during the war as they were not yet married into the Brook clan. Surprisingly if you compare a list of their missions, 6 of them are on both lists.

14 Oct 44 to Duisburg

14 Oct 44 to Duisburg

28 Oct 44 to Cologne

30 Oct 44 to Cologne

30 Nov 44 to Duisburg

04 Dec 44 to Karlsruhe

The 14 Oct 44 raids to Duisburg seemed to involve nearly the entire RAF bomber force but the other raids were not so large. It is therefore just a odd coincidence that they both flew to the same place on the same night. Dave kept excellent notes on his time in the RCAF and he wrote a little Novella some years ago where he put it all down on paper.

Dave wrote about the raid to Cologne on 30 Oct 44,

Two days later on October 30 we went back to Cologne on a night OP. we were airborne at 5:22 pm and arrived at the target right on time at 8:16 pm. the pathfinders did a good job of target marking and Fred (the bomb aimer on Dave’s Halifax) did a good job of bombing. Our target pictures showed that we had knocked out a large German power plant. The pictures clearly showed the outlines of the wrecked building and four large smoke stacks lying on the ground. Right after we turned to start for home we had the scare of our lives when we were coned by searchlights. The inside of the plane was so bright that the light seemed almost solid and tangible. You felt like you could pick it up in your hands. Andy and John Daly (the pilot and flight engineer) had worked out a strategy to prepare for this event. They cut the power on all four engines and put the plane in almost a straight down dive. This got us out of the cone momentarily at which point Andy made a steep turn to port for a few seconds and then a steep turn to starboard. This did the trick and the lights failed to find us again.

Isn’t it interesting that Dave is complementing the job of the pathfinders on this raid and as it turns out, his complement is directed towards his future relative.

Towards the end of 1944, both Dave an Allan began to see ME-262’s, Germany’s revolutionary jet fighter in action against their planes. It was truly frightening to be attacked by a plane that was far faster than the escort fighters that accompanied the bombers. On their joint 4 Dec 44 to Karlsruhe, they both reported seeing jet fighters for the first time.

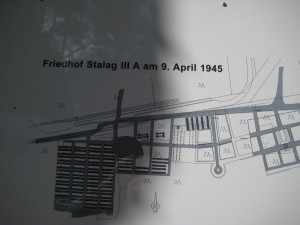

On 5 Jan 45, Dave’s crew was on the return flight after having bombed Hannover when the plane was hit by 20 mm cannon fire from a German night fighter. Only Dave and two other crew members were able to get out before the plane exploded. Dave ended up at Stalag Luft 3A near Lukenwalde. The camp included a British and American Officer’s section as well as a section for Russian POW’s and another for other Europeans and civilians. As the Russians pressed towards Berlin from the east and the western allies pressed towards Berlin from the west, the Germans began moving POW’s from camps that would have been overrun. Dave’s camp thus began to fill with prisoners from many other POW camps.

He wrote:

At the end of January 1945, a large group of RAF officers arrived from the famous Stalag Luft 3B in Sagen, Silesia. There were over 1000 men and completely filled up our compound. This camp had been the site of the “great escape” followed by the murder of a large number of prisoners by the Nazis (54 to be exact). these officers were evacuated before the advancing Soviet armies and were forced to march the several hundred miles to our camp in winter weather. They experienced great hardship in doing so. Some were in pitiful condition on their arrival.

There were also a number Polish officers in the camp that were captured right at the start of the war. Dave befriended three of them and they used to meet on the sports field to converse. They spoke German and Dave could speak some German mixed with Yiddish. They soon all figured out that they were all Jewish. One of them, Julian Wilf gave Dave a photo of himself which Dave kept his entire life. Dave never knew what happened to his friend after the war.

Life in the camp was pretty boring. To keep themselves busy they thought a lot about food and spent a lot of time trading the items in their red cross parcels amongst themselves and with the German guards. They all seemed to take a perverse delight in making life difficult for the guards by always showing up late for roll call or moving around to screw up the POW count.

One amazing story that Dave included in his writing was about having a Jewish religious service on a Saturday. Since I could not make this up even if I tried, I’ll just let Dave tell it in his own words:

A regular feature every Sunday morning at our camp was a Christian church service which took place on the sports field rain or shine. A Catholic chaplain who had been taken prisoner conducted these services for both Protestants and Catholics. A Jewish American B-17 pilot, who was quite religious approached me one day and asked if I would be interested in participating in a Jewish service if it were held on Saturdays. I told him that I was not particularly religious but that I would be glad to help form a Minyan (10 men needed to have a service). Since I was the only British Jew in the compound, he asked me if I would discuss the matter with the RAF Group Captain, since he was the senior allied officer. I agree and we both spoke to him. The Group Captain wondered if this was a wise thing to do, knowing the German attitude towards Jews. We told him that we were prepared to risk it as we did not think that there would be a big reaction this close to the end of the war. He then stated that he would back us up but that we had to understand that he had very little power or authority to help if things turned bad. We accepted this and thanked him for his kind interest in the matter. The American pilot had already rounded up enough American Jews to form a Minyan with myself. the Polish Jews were not approached since their position was too precarious. The American pilot had a prayer book….. We decided to hold our Jewish service the very next Saturday. The day proved to be bright and sunny, which we took as a good omen. After breakfast and the Appell we gathered on the sports field and formed a small group facing east. Our religious leader began the service. The rest of us followed suit as best we could. A crowd of curious prisoners soon gathered around to watch. A patrolling German guard came by and after a while and demanded, “was ist los?” (what’s goign on?) When told that we were conducting a Jewish Church Parade , he explaimed, “nich erlaubt” (not allowed). We ignored him and continued with our service. He then ran off to the Headquarters building. Soon afterwards a file of about ten German soldiers, came running towards us carrying rifles with fixed bayonets. On seeing this, the crowd of prisoners around us, which had grown to several hundred, immediately stepped forward and joined us in our prayers, genuflecting and humming as best they could. This stopped the Germans in their tracks. A sergeant with them went off to confer with an officer and the order came down for them all to withdraw which they soon did. This was the last that we heard from the Germans about this matter and we continued to hold our services until we were liberated by the Russian army several weeks later. This was probably the only organized Jewish religious service being held in Germany at this time.

I visited the camp in 2011. Not much is left except a small memorial park and some undeveloped fields where you can see some remnants of the camp’s huts.

After the war, both Allan and Dave returned to Canada. Both entered medical school. Dave became a Plastic Surgeon in Montreal and Allan was a GP in a small town in Saskatchewan, North Battleford. They both had families, lived their lives and are remembered by those that knew them. Allan passed away in the 1980’s but Dave lived into his 90’s and just passed a few months ago.

We remember their service.