By Richard Brook

They came from every part of the state. From Texarkana to El Paso, from Amarillo to Beaumont, from Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Austin, and everywhere in-between. They came for a variety of reasons. Some simply were looking for work while some came for adventure. Many came for the opportunity to fight the Nazis when America was still sitting on the sidelines.

They came in 1939, 1940 and 1941, before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

They came to Canada to train in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) before travelling to England to fight the Nazis.

More than 8800 Americans, including nearly 1000 from Texas joined up before America entered the war. 829 of these intrepid, courageous RCAF Americans were killed-in-action during the war. Of these, around 50 Texans would make the ultimate sacrifice and never return to their beloved Texas.

This is a story of the men who left Texas and America to join the fight against tyranny when their own country was still uninterested in doing so.

On September 10, 1939, Canada declared war on Germany and Italy, more than 2 years before the United States joined the war herself. The RCAF immediately recognized the need to train thousands upon thousands of airmen for the coming air war and Canada became the home of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Before the war’s end, Canada would train more than 130,000 airmen at more than 200 small airports and landing fields across the country.

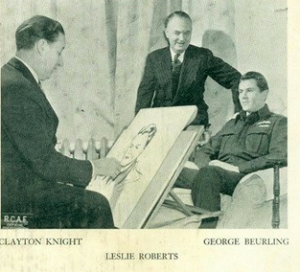

Finding enough men to fill all the spots was an immediate and enormous problem. Canada’s Air Marshall Billy Bishop, a hero from WW1, had an idea. He contacted his old friend from WW1, Clayton Knight, an American who had flown with the British during the war. The two of them came up with the idea of smuggling American pilots into Canada for the purpose of training them to fight in the RCAF. They knew this was illegal and a complete violation of US Law, but this “minor impediment” did not dampen their enthusiasm for the idea.

Their first effort was aimed at recruiting pilots from American flying schools. They soon had a list of some 300 pilots willing and eager to come to Canada and join the fight. Not wanting to immediately incur the wrath of the US Government, they quietly sought and received permission in Washington for their plan so long as they kept it quiet. So far, so good. No one wanted these men to be prosecuted for fighting in a foreign army or for violating the US Neutrality Act. Nor did they themselves wish to be arrested for recruiting Americans to fight for a foreign army while on American soil.

When Roosevelt won reelection in November of 1940, the Clayton Knight Committee kicked into high gear. They set up recruiting offices in New York’s Waldorf Astoria and in other hotels in Atlanta, Cleveland, Memphis, Kansas City, Dallas, San Antonio, Spokane and Los Angeles. Even though advertising was by “word of mouth” only, the results were impressive and recruits came pouring in. Of course everyone knew that what they were doing was totally illegal and with hundreds of Americans heading to Canada, the Canadian government soon became more and more nervous about the entire plan.

So they all cooked up a new idea. The Clayton Knight Committee recruits were told they were being recruited for civilian flying jobs at a company called the Dominion Aeronautical Association, something totally legal. When they arrived in Canada and walked into the DAA offices, the person there apologized and told them that there were no longer any civilian jobs available. But they were then told, “it just so happens that there is an RCAF recruiting office next door and they have plenty of jobs”.

By December of 1941, more than 6000 American aircrew were actively flying in the RCAF or on loan to the Royal Air Force (RAF) in England. By the time the war ended in 1945, a total of 8,864 Americans served in the RCAF with nearly 900 killed in either training accidents or in combat. They flew mostly in Halifax, Wellington and Lancaster bombers. But they also flew Spitfires and Hurricanes and every other type of craft available at the time. Of those who died in the war, roughly half perished while flying in RCAF squadrons while the other half perished while flying in RAF squadrons.

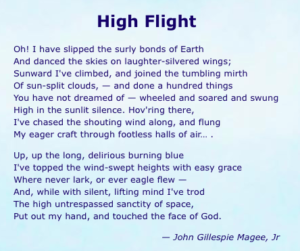

Of the RCAF Americans who flew fighters, many will know the name John Gillespie Magee. Magee died in a training accident in England on December 11, 1941 while flying a Spitfire with RCAF 412 Squadron. He is remembered for his famous poem, High Flight, which Ronald Reagan borrowed from in the speech that he gave immediately following the Challenger disaster in January, 1986.

Some of the RCAF Americans who wanted to be fighter pilots ended up serving in one of three American Eagle Squadrons. Nearly 750 Americans served in these squadrons before the squadrons were transferred to the fledgling US 8th Air Force after the US entered the war. A majority of these pilots also passed through the Clayton Knight Committee recruiting offices, then to the Dominion Aeronautical Association and ultimately into the waiting arms of the RCAF and RAF where they were trained before deploying to England in one of the three Eagle Squadrons.

After the US entered the war, the RCAF Americans were heavily recruited by the USAAF to return to American squadrons. Some agreed and transferred to join US Squadrons while many chose to stay in the RCAF and continue to fight with their RCAF and RAF comrades in arms.

Many served with great distinction.

John Harvey “Crash” Curry was born in 1915 in Dallas. By the mid-1930’s, Curry was barnstorming around Texas giving flying lessons to anyone with the money to pay for them. He attended Air Corps Primary Flying School at Randolph Field in San Antonio before enlisting on the 27th of August 1940 in Ottawa, where he was immediately commissioned as a Flying Officer. Curry flew Spitfires against the Luftwaffe in 1941 and 1942. He became a squadron leader in Egypt, leading the 80th Squadron in June of 1943. As the war progressed, the Squadron moved to Italy in early 1944. On March 9, he was shot down while strafing a column of German tanks. After successfully bailing out, he hid out in the Italian countryside with other downed flyers, all of whom were sheltered by friendly Italians. Cold and hungry, he finally made his way back to Allied lines on March 18 where he soon resumed his flying career. For his gallantry during the war, Curry received a Distinguished Flying Cross and was made an Officer in the Order of the British Empire (OBE).

One of the more colorful RCAF Americans was Flight Lieutenant William Ash, also from Dallas who graduated from the University of Texas in Austin. Ash enlisted in the RCAF in Windsor, Ontario, across the border from Detroit in 1940. He was assigned to No. 411 Squadron RCAF where he flew many missions in a Spitfire including an attack on the German Battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. He was shot down over Calais on March 24, 1942. The French resistance found him before the Germans and smuggled him into Paris where he hoped to join a long line of allied airmen trying to make their way back to England. He was captured in Paris at the end of May of 1942 and sent to a POW camp. Over the next 3 years, Ash would successfully escape 4 different times from 3 different POW camps. Each time he escaped, he was recaptured before he could make his way to safety.

Most famously, he ended up in Stalag Luft IIIB in Zagan (now in Poland) where he found himself in the middle of the planning for what became known as the “The Great Escape”

In 2014, after Ash passed away, the BBC did a story on him where they wrote that Ash was the model for Virgil Hilts, the character played by Steve McQueen in the famous 1963 movie.

As did the Hilts character, Ash endlessly persisted in trying to escape and, as a result, he spent a lot of time in the camp’s prison block or “cooler” as it was called. Many times during his life, Ash humorously denied the claim that he was the model for the Hilts character by saying that he never made an escape where he stole a motor cycle and headed to Switzerland. He also pointed out that he did not actually participate in the “The Great Escape” because he was already locked up in the “cooler” at the time as punishment for a previous escape attempt.

In May of 1946, Ash was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire. He stayed in England after the war and became an author.

Lance “Wildcat” Wade was born in Broaddus, TX in 1915. He crossed the Canadian border in December of 1940 and ended up in the RAF. He joined #33 Squadron in Egypt, where his skill and daring resulted in 2 enemy kills in a single day in November of 1941. By September of 1942, with his first tour of duty completed, Wade returned to the United States. He toured training facilities and participated in some war bond drives and was even photographed with President Roosevelt. He returned to North Africa in January 1943 as a flight commander in #145 RAF Squadron. By the time he finished his second tour of duty, Wade had shot down more enemy planes than any other allied pilot in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations with kills over Tunisia, Sicily and then Italy. Wade received a promotion to Wing Commander and joined the staff of Air Vice Marshall Harry Broadhust of the RAF’s Mediterranean Command. Sadly he died in a plane accident in Southern Italy on January 12, 1944. He was the highest-scoring American pilot to serve in the RAF with 25 victories.

After Wade’s first tour of duty the USAAF offered him a higher rank and more pay if he would resign from the RAF and join the USAAF. But he turned them down, instead saying, “Thanks, that’s mighty fine, but I’d rather keep stringing along with the guys I have been with for so long now.”

One RCAF American who did resign from the RCAF to join the USAAF was 1Lt Floyd Magnum McRoberts of Fort Worth. Floyd joined the RCAF in 1940 and flew as a gunner in a Wellington and then a Halifax Bomber. After receiving his USAAF service number, he was told that the USAAF had so few planes in Europe that he should stay in his current RAF #429 Squadron. Floyd never left the Squadron and was killed when his bomber was shot down over Osnabruck, Germany in December of 1944. Osnabruck was a frequent bombing target in the Rhineland as there was much heavy industry in the area. Records indicate the tail number of his Halifax Bomber was MZ463.

By war’s end, 829 RCAF Americans had been killed-in-action, some 50 of them from Texas. As often happens during a war, the records are not complete. Many of the families of those who died never received a full and complete explanation of what happened to their father or son or brother.

George Bentinck, of Galveston was killed-in-action while flying in a Lancaster Bomber. His family says that he went to Canada in 1940 to join the war out of a sense of adventure. They received news of his death late in 1944 after his plane was shot down over Germany.

For American Servicemen killed in WW2, it was common practice for the families to have the option of returning the remains of their family member to the USA or to inter the remains in one of America’s Military Cemeteries in Europe. That was not the tradition in the RCAF and RAF where nearly all of the RCAF and RAF Americans who were killed-in-action are interred in one of the many Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemeteries (CWGC) scattered around Europe. As with the American Cemeteries in Europe, the CWGC meticulously maintains these Cemeteries. At the entrance to each, in a small brass box, there is always a book that contains whatever is known about each of men resting in the cemetery. For some, much in known including the names of their parents or wives, their home towns and sometimes even something about when and how they were killed-in-action. For others, the book only includes their name, rank, and service number.

George Bentinck (age 21) from Texas is buried in the Durnbach War Cemetery where he rests as Warrant Officer 2nd Class with service number R/137457 in the RCAF. He was killed-in-action on February 25, 1944. The Durnbach Cemetery is about 30 miles south of Munich and contains the graves of 2971 men, almost all airmen.

Two men from Austin, Flight Sergeant Seth Glasscock and Flight Officer George Woolrich were both killed-in-action during the war while flying Spitfires. Both are memorialized at the Runnymede Air Forces Memorial, near Windsor and not far from Heathrow Airport, where the names of more than 20,000 airmen whose bodies were never recovered, are listed.

Clarence Wisrodt of Galveston joined the No 17 Squadron and flew in a Halifax Bomber. In November of 1941 his Squadron was loaded onto ships and sailed for Singapore. Before they could arrive, the Japanese entered the war and his Squadron was diverted to Burma. Sergeant Wisrodt was killed-in-action on March 3, 1942 while fighting the Japanese in Burma. His name is memorialized at the CWGC Memorial in Singapore.

In 2006, a retired Air Canada pilot Karl Kjarsgaard and presently a Director of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, began researching the subject of RCAF Americans in the Canadian archives. The names of hundreds of Americans who perished while in the service of the RCAF and RAF have been identified. Karl began publicizing this work in 2012 and it wasn’t long before he and his colleagues at the museum began hearing from American families that knew that their family member had gone to Canada before the US entered the war, to fight the Nazis. Sadly, that is often pretty much all they knew.

In 2013, the State of Virginia built a first memorial honoring the 16 Virginians who fought and died as RCAF Americans.

In Jan. 2016 a Florida state memorial and plaque was dedicated at the Winter Haven Municipal Airport to the 6 RCAF Floridians killed-in-action in the RCAF.

In Colorado, Aviation Historical Society is planning to include the 6 RCAF Americans from Colorado who were killed-in-action with a possible ceremony in the fall of 2017.

In September of 2016, Congressman Tim Ryan (D-OH) sponsored HR-5887, the RCAF/RAF-Americans Congressional Gold Medal Act. The Bill never reached the floor before the House adjourned at the end of December. With the new 115th United States Congress that went into session on January 3, 2017, plans are being made to reintroduce the bipartisan bill to honor these men who deserve recognition for their valiant service in the RCAF and RAF.

Please forward this article to your Congressman and ask him or her to help push the new bill through Congress when it comes to the floor.

These men and their families deserve recognition for their actions some 75 years ago.

Information for this article was provided by Karl Kjarsgaard and the team at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada located in Nanton Alberta, Canada.

Further information about the men who perished as RCAF and RAF Americans was taken from the book “They Shall Not Grow Old” by Les Allison and Harry Hayward.