23 February 2015 is the 70th anniversary of the raising of the US Flag on Mt. Suribachi on the tiny island of Iwo Jima.

Fighting our way to Iwo Jima had already taken a herculean effort. After Pearl Harbor, the Empire of Japan seemed unstoppable and the news only came in one kind…. bad. Wake Island fell to the Japanese on 23 December 1941. On 9 April 1942, the American troops surrendered on Bataan. Nearly 90,000 Phiippino and US troops surrendered in what was the largest surrender of US troops since the Civil War. A month later, Corregidor fell to the Japanese. On 15 May 1942, Burma fell. The expansion continued with Hong Kong, Borneo, and Singapore. By 31 August 1942, the Caroline Islands, the Gilberts, the Marshalls, the Marianas, and the Solomon Islands would all be occupied and controlled by the Japanese. The Japanese even bombed Darwin in Australia on 19 February 1942. The Japanese had already occupied much of China. Was Australia next?

Although the Japanese would suffer a serious set back at the Battle of Midway in June of 1942, it was only after a terrible fight on Guadalcanal that began in August of 1942 and ended in February of 1943 that the US and its allies could finally stop Japanese expansion. The fight on Guadalcanal took a tremendous toll on the US Navy and Marines. Two aircraft carriers were lost, the Wasp (15 September 1942) and the Hornet (27 October 1942). This left only the USS Enterprise functioning in the entire Pacific. And it too was damaged before the end of the year. The situation was so bad that news of the loss of the Hornet was only made public in January of 1943 after several new aircraft carriers started to come into service.

Thus beginning in early 1943, after successfully beating the Japanese on Guadalcanal, the long island hopping campaign towards Japan could begin. But it was a long and bloody affair. More than 30 island invasions were undertaken with more than 70,000 killed and 300,000 wounded. As the allies closed in on Japan, the Japanese became more and more desperate and more and more fanatical. In many instances, rather than surrender and after they were out of ammunition, they would often charge the US lines in Banzai charges. First at night but then also during the day, with swords drawn, they often charged into the US lines. There was no surrender. It was “kill or be killed”.

At Saipan, things would take an even darker turn. Beginning on 15 June 1944 and for the next three weeks, 71,000 Marines fought it out against a force of 31,000 Japanese. When it was over24,000 Japanese soldiers were dead and another 5,000 had committed suicide. But 3500 Marines also lay dead with another 10,000 injured including the actor, Lee Marvin.

In one final banzai charge, some 3,000 Japanese ran towards the US lines. Behind them came all the wounded, some only barely able to walk. Some on crutches. The US front line was over run and 2 army divisions were almost totally wiped out with some 650 killed and wounded. The attack lasted more than 15 hours after which more than 4,000 Japanese lay dead. Three men were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, all posthumously.

To the Marines, Navy and Army personnel who participated in this, what must they have been thinking? How much worse could it get?

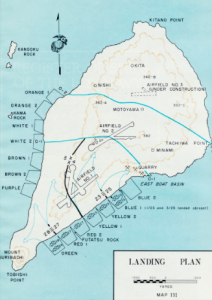

Sadly it could get a lot worse. Six months after Saipan, it was now time to invade Iwo Jima, Over the course of 5 weeks beginning on 19 February 1945, 70,000 Marines took on 22,000 Japanese. The Japanese had dug more than 11 miles of tunnels dug into the hills, the coral, and the sand of an island that only measures 8 square miles.

At the southern tip of the island stood the islands largest feature, Mt. Suribachi at 500 ft. above sea level.

Following a massive bombardment that lasted for hours from both naval artillery and bombers, the first of 30,000 Marines landed on the south east side of the island. The landing was uneventful and the Marines thought that perhaps all the Japanese died in the bombardment. Successive waves of Marines landed behind the first wave as the Japanese were waiting for just the right moment to open fire. The Marines were caught in a withering cross fire of Japanese artillery, mortar and machine gun fire. It was impossible to dig a fox hole due to the soft sand. All they could do was move forward which took them into more direct lines of fire from the hidden Japanese. Making things worse, US tanks also driving off the beach began to run over Marines who could not get out the way. By the end of the first day, the US had already suffered more than 2400 casualties. Progress was made yard by yard as the Marines moved across the island as well as south towards Mt. Suribachi. Only the prodigious use of flame throwers could suppress the gun fire coming from the well Japanese positions. The battlefield looked like a World War I battlefield with the massive use of artillery turning the entire area into a killing zone where bodies could only be identified by fragments of their uniforms.

One Navy Chaplain, Gage Hotaling, recalled burying “fifty at a time” in bulldozed plots where the bodies were so mangled that he had no idea if the men were Jewish or Catholic or something else. He attended to 1800 burials himself.

John Bradley, a Navy Medic, found himself in the middle of all of this trying to save the wounded. On the second day of the fight Bradley ran out into the open field to save a badly wounded Marine. He managed to apply field dressings and was able to pull him back to safety. For his efforts, he was awarded the Navy Cross. But the emotional scar left behind from the fight kept Bradley from ever talking about Iwo Jima with his family.

On the second day, the Navy finally landed a large number of tanks which provided the Marines with some cover from the machine guns as they began to advance towards Mt. Suribachi.

The Marines also benefited from a new technical development. Finally, after numerous island invasions, someone had figured out that if the men on the ground were in direct radio contact with fighters circling above, then those fighters could actually be called upon directly to swoop down and attack enemy positions with immediate effect. Readers today will shake their head and wonder how such a seemingly obvious arrangement had not previously been implemented. But shockingly, it was totally uncommon for pilots to talk directly to ground troops or for the pilots to send a forward air observer to speak directly to them and call in targets of opportunity. In fact, the only reason that it happened at all was because the pilots and Marines were all living together on the Navy ships. Finally, in frustration, some pilots and Marines began to talk about improving tactics. The end result was to give the pilots and Marines radios set to the same frequency so that they could talk to each other directly. Prior to this. the Marines had to radio for help back to the ship. On board the ship, the Marine radio operator had to write down the request for assistance and hand it to the Navy person who was in radio communication with the pilot. Only then was a request sent to a pilot to fire on a certain location. This often 10 minutes or more by which time the situation could be completely different.

On D-Day+4, 41 men were working their way towards the summit of Mt. Suribachi. They had been given a flag and told by their Colonel that should they reach the summit, they should raise the flag. Each of the 41 men thought that their next step forward was going to be their last step. But finally they made it to the top and began looking for a way to raise the flag. Unknown to them, every person on the island and every person onboard the several hundred ships with a view began to watch the drama unfold. The men attached the flag to a pipe and Lt. Schrier, Sgt. Thomas, Sgt. Hansen, Cpl. Lindberg, and Pt. Charlo raised the flag. Suddenly they could hear the cheers from the Marines below them and ships off shore began to blow their horns. The Japanese noticed this too and immediately opened fire on the men at the summit. As they dove for cover, the photographer, a Sgt. Lowry, broke his camera but not before he took this picture below:

Onboard one of the ships, Navy Secretary James Forrestal was watching with Marine General Holland Smith. Somehow Forrestal got it into his head that he wanted the flag as a souvenir. But the Colonel who had sent the men up the hill in the first place, also wanted the flag so he ordered that another group of men should take another flag up to the top of the summit before Forrestal could lay claim to it. And Colonel Chandler Johnson ordered his men to take “a much bigger flag” to replace the one he wanted.

They say that the 2nd flag had flown from a ship that was sunk at Pearl Harbor. No one is really sure if that is true but it was carried to the summit by Ira Hayes, Franklin Sousley, John Bradley, Harlon Block, Mike Strank and Rene Gagnon. An AP photographer, Joe Rosenthal happened to hear that another flag was on its way up and he decided to tag along. On the way up, the group with the 2nd flag and Rosenthal passed St. Lowry who had just taken his picture and who was heading down to replace his smashed camera.

Almost immediately upon reaching the summit, Rosenthal realized that the 2nd flag was about to raised and he quickly jumped into position. The 2nd group of flag raisers had also attached their flag to piece of pipe but because of the size of the flag and the strong breeze, it took all of them to manhandle the pipe into the vertical position. Just as they were pushing the pole upwards, Rosenthal snapped his iconic image.

The photo would become the most reproduced photo of World War II. Rosenthal would earn a Pulitzer Prize for his work.

It has been reproduced in many forms the most important of which is the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington Cemetery outside Washington, DC. The original mold is located on the grounds of the Marine Military Academy in Harlingen, Texas.

Sadly, within just a few days, Harlon Block, Franklin Sousley and Michael Strank were all killed in action. Gagnon, Hayes and Bradley became celebrities and toured the country with a model of the flag raising that was used in the largest and most successful war bond drive of the entire war, raising more than $26 Billion, twice the goal.

Ira Hayes, following the war, suffered from what we now call PTSD. He developed a heavy drinking problem and died in 1955. Tony Curtis played Ira in a movie called The Outsiders in 1961 and Johnny Cash recorded a song about him called “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”. Rene Gagnon returned to Iwo Jima on the 20th anniversary of the battle in 1965. He passed away in 1979.

John Bradley never talked about his war time experiences with his family. EVER. He only gave one interview, in 1985, about the subject. When he passed away in 1994 his son James knew almost nothing about his fathers experiences during the war. It was a taboo subject when he was growing up. Eventually he found a trunk at home with some of his father’s things from the war and only then began to think about learning more about it. He went on to publish a book “Flags of our Fathers” in 2000. Clint Eastwood used the book to inspire a movie with the same name in 2006.

Iwo Jima was the only battle in the entire Pacific Campaign where US casualties exceeded Japanese dead. 26,000 Americans were killed or wounded on Iwo Jima with another 10,000 Navy personnel killed or wounded in the surrounding ships from Japanese attacks from the air including Kamikaze attacks. Of the 22,000 Japanese, only around 200 were taken prisoner, almost all of these were captured after being knocked unconscious during the fighting.

Iwo Jima was still not the end of the Japanese Empire. Okinawa was invaded on 1 June 1945. Over the next six weeks, more than 50,000 Americans were killed or wounded on the island and another 15,000 were killed or wounded in the waters surrounding the island on the Navy ships. More than 110,00 Japanese soldiers were killed and another 100,000 Japanese civilians also perished, often by suicide.

Compared to Okinawa, Iwo Jima suddenly started to look like a picnic. And every single American in the Pacific began to look at an upcoming invasion of the Japanese Home Islands thinking that none of them (neither American or Japanese) would ever survive it.

Luckily for them all, at a number of undisclosed locations around the US, very clever people were at work on a device which they hoped would be so horrific that it would force the end of the war. It took using two of them, but it finally brought Japan to their senses and no invasion of Japan would occur.

Over the course of WW II, nearly 400,000 US servicemen would be killed. This number is roughly split 50/50 between the Pacific and Europe. Iwo Jima was the only battle where US casualties exceeded Japanese casualties and nearly 1/4 of all Congressional Medals of Honor awarded to Marines in the Pacific were awarded to men on Iwo Jima. 27 awards were made, 14 of them posthumously.

John Basilone was killed on Iwo Jima on the first day. He received both the Congressional Medal of Honor (Guadalcanal) and the Navy Cross. (Iwo Jima). He was the only Marine enlisted man to receive both awards.